LITHIC

CASTING LAB

Pete Bostrom

The following article will offer some background information about Lithic Casting Lab and how it began. It's from a 1998 April issue of "Mammoth Trumpet." A publication that is devoted to the study of the Earliest Americans and published by The Center For The First Americans.

THE Art OF PRESERVING ANCIENT SKILLS

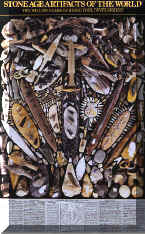

The "Stone Age Artifacts Of The World" picture will probably

always be my favorite. It took two weeks to lay out. But it also took months to coordinate the project,

working with large and small collections from

across the country. The largest collection was the Smithsonian Institution

and the smallest were private collections. What is most exciting about this picture is that these artifacts represent a span-of-time

in which all humans have existed. They also show how complex stone tool

technology really was. There are two bifaces (large blades) in this

picture, the "Sweetwater Biface" and a 24" biface from Mexico that no one has yet been able to duplicate in

modern times. They are good examples that illustrate how skillful some of

these early flintknappers were in making stone tools.

The entire Industrial Revolution has only lasted no more

than the life time of two people, if they lived to the oldest age and

back-to-back. But the Stone Age lasted for millions of years. If it wasn't

for the long lasting durability of stone our knowledge of the past

would be greatly diminished.

"The

Art Of Preserving The Past"

April 1998

"Mammoth Trumpet" By Carol Ann Lysek

(Abbreviated Version)

If you were to visit the world's largest repository of molds and master

molds of important Stone Age tools you would have to travel through the

southern Illinois cornfields to Troy, Illinois, for it is there that Pete

Bostrom operates his Lithic Casting lab.

Known internationally in archaeological circles for the

high quality of his casts of Stone Age artifacts, Bostrom has devised many

of his own methods in what has evolved into a complex multi-step casting

process that ultimately results in molds, master molds, and finished casts

that look almost exactly like the original artifacts. Bostrom believes he

is probably the only person doing this specialized craft as a full time

occupation.

The Lithic Casting Lab "has in the past"

specialized in the replication of prehistoric stone artifacts for museum

displays, teaching aids, reference collections, and for special situations

such as casting artifacts that will be damaged when samples are cut from

them for thin-section or obsidian hydration dating analysis. Bostrom has

also molded and cast artifacts that need to be examined under a scanning

electron microscope but will not fit inside the instrument; selected areas

for study can be cut from the cast and the artifact itself is left whole.

Learning

how to maintain good edge detail and how to cast large items so that they

are detailed and free of air bubbles has taken the 49 year old Bostrom

years of trial-and-error experimentation. He told Mammoth Trumpet that he

has never heard of anyone else doing some of the procedures that he does.

It's an expensive and time-consuming process, but over

the years he has cast hundreds of artifacts from many federal agencies

including Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, Forest

Service, National park Service, and the Smithsonian Institution. He has

done casting projects for a large number of states, counties, museums and

universities. His casts inevitably cause excitement-and-sales among

collectors, flintknappers and within the professional

community.

Bostrom's interest in archaeology dates back to his

childhood. He began surface-collecting artifacts in Illinois in the

early 1970's. After serving in Vietnam, he returned to his job at General

Motors and in 1973 built a 70 by 26 foot building that he used to raise

and sell tropical fish. An influx of fish imported from Asia made fish

breeding impractical, so he returned to his original interest-archaeology.

Bostrom was employed for more than 21 years by General

Motors, and it was only in 1987 that he took an opportunity to leave and

begin to work full time casting artifacts.

Finding himself interacting daily with Old World and

New World archaeologists, collectors and flintknappers, Bostrom learned

that these four groups often have conflicting points of view, but he says

that each has something valuable to offer.

The most unusual cast that Bostrom ever did was a

series of Bigfoot tracks that belonged to the Forest Service. In about

1985 he made molds of three plaster casts of large footprints discovered

in Washington state that showed visible dermal ridges and sweet pores--one

of the prints showed a flexible foot bending around a rock. Bostrom is

amazed at the number of people he meets who have stories about Bigfoot. He

says they make for great campfire conversations.

Bostrom has accumulated thousands of master molds and

casts of artifacts from cultures worldwide over a 25-year period. At least

46 Paleo-Indian sites are represented in the collection, including Mesa

and Moose Creek, Alaska; Blackwater Draw, Colby, Domebo and Drake in the

West; Bostrom and Kimmswick in the Midwest; Dutchess Quarry Rock shelter,

Thunderbird and Vail in the East. He also has molds of artifacts from

important Old World sites such as Abbeville in France, Kalambo Falls in

Zambia, Mezhirich in Ukraine and Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania.

Years ago Bostrom decided that he also needed to make a

photographic record of some of the more uncommon artifacts that were

coming through his laboratory. He has perfected a method for depicting

both sides, as well as an edge view of an artifact, in a single

photograph. Using a large-format camera, he takes a triple exposure on a

4x5 negative. He then transfers the image to a slide that presents the

'impossible" perspective of all three views at once. He uses an 8x10

inch camera when photographing artifacts.